Reading to Learn

Jacobs explains that students learn and practice beginning reading skills through about the third grade, building their knowledge about language and letter-sound relationships and developing fluency in their reading. Around fourth grade, students must begin to use these developing reading skills to learn — to make meaning, solve problems, and understanding something new. They need to comprehend what they read through a three-stage meaning-making process.

It’s not uncommon for a struggling secondary reader to declare, “I read last night’s homework, but I don’t remember anything about it (let alone understand it)!” According to Jacobs, “How successfully students remember or understand the text depends, in part, on how explicitly teachers have prepared them to read it for clearly defined purposes.”

During the prereading stage, teachers prepare students for their encounter with the text. They help students organize the background knowledge and experience they will use to solve the mystery of the text. To do so, they must understand the cultural and language-based contexts students bring to their reading, their previous successes or failures with the content, and general ability to read a particular kind of text. Based on this assessment, teachers can choose strategies that will serve as effective scaffolds between the students’ “given” and the “new” of the text.

Asking such questions as, “What do I already know and what do I need to know before reading?” or “What do I think this passage will be about, given the headings, graphs, or pictures?” helps students anticipate the text, make personal connections with the text, and help to promote engagement and motivation. Brainstorming and graphic organizers also serve to strengthen students’ vocabulary knowledge and study skills.

Stage Two: Guided Reading

Students move on to guided reading, during which they familiarize themselves with the surface meaning of the text and then probe it for deeper meaning. Effective guided-reading activities allow students to apply their background knowledge and experience to the “new.” They provide students with means to revise predictions; search for tentative answers; gather, organize, analyze, and synthesize evidence; and begin to make assertions about their new understanding. Common guided-reading activities include response journals and collaborative work on open-ended problems. During guided reading, Jacobs recommends that teachers transform the factual questions that typically appear at the end of a chapter into questions that ask how or why the facts are important.

The ability to monitor one’s own reading often distinguishes effective and struggling readers. Thus, guided-reading activities should provide students with the opportunity to reflect on the reading process itself — recording in a log how their background knowledge and experience influenced their understanding of text, identifying where they may have gotten lost during reading and why, and asking any questions they have about the text. As with prereading, guided-reading activities not only enhance comprehension but also promote vocabulary knowledge and study skills.

2. Phonics

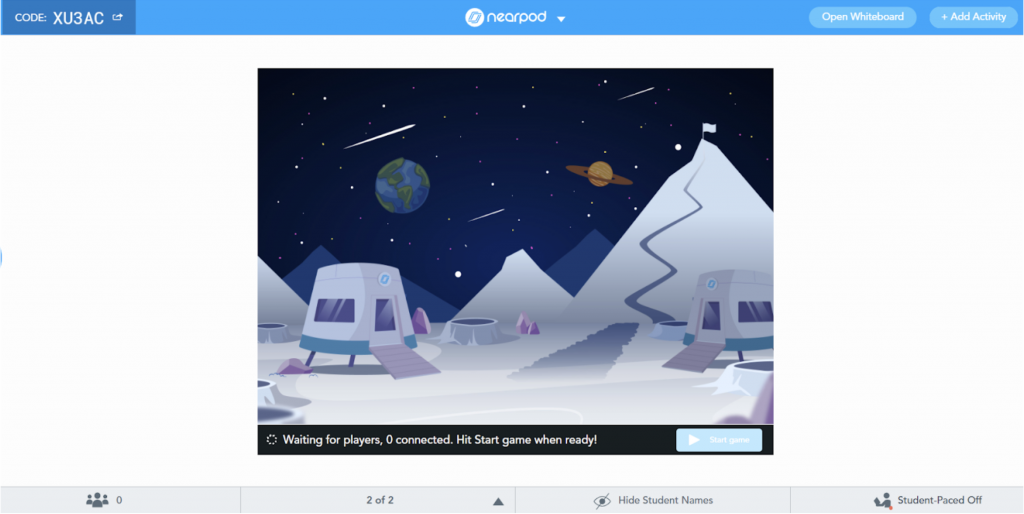

If the Science of Reading tells us anything, it’s that phonics must be systematic and explicit. Never leave students guessing. Inside the classroom, student’s work at various spelling levels. What teachers need most are phonics lessons that are easy to create and differentiate for all learners inside the classroom. Spending hours in front of the copier or cutting out game pieces for said activities isn’t ideal or efficient. Plus, teachers have to store all those games somewhere. Nearpod activities take so little time creating, and once teachers make a lesson, it can act as a template for more differentiated activities. Here are a few lesson ideas for phonics instruction:

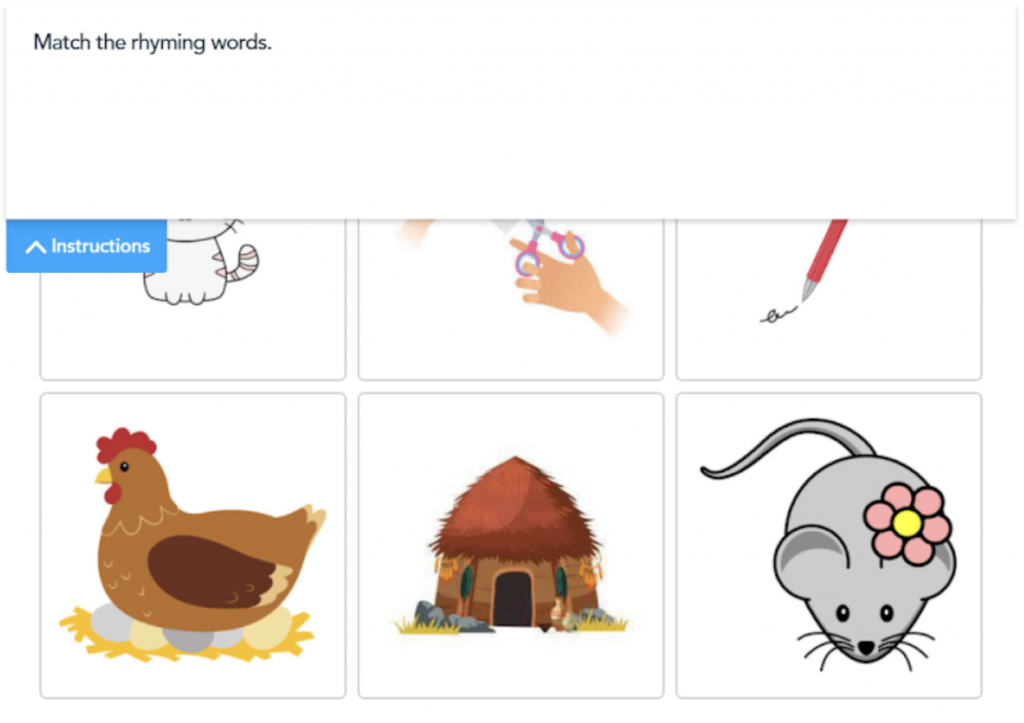

- Use Drag and Drop for students to create word sorts based on spelling patterns, prefixes and suffixes, and syllable types. For example, have students sort the three sounds of -ed, or -sion, -tion.

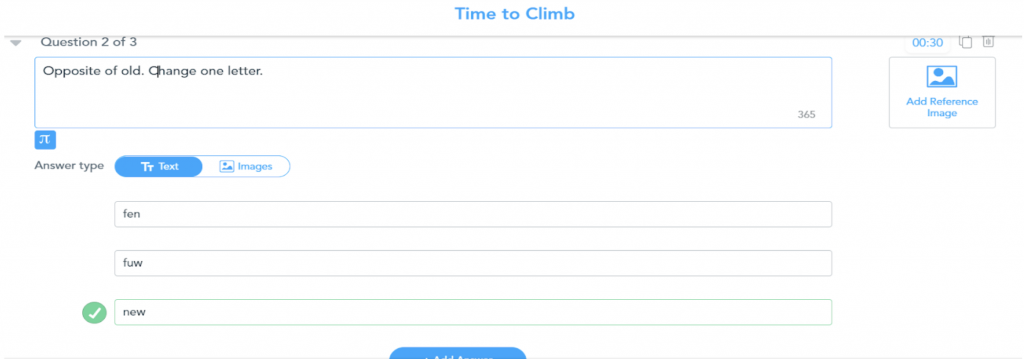

- Use Time to Climb to engage students in spelling. Answers developed vary from written to using pictures. Make word chain questions to keep students on their feet with multiple spelling patterns. Have students start with spelling “meat” then have the next question be “Would you like to ____________ after school?” Gets more complex spellers higher level thinking, but in fun ways.

- Create vivid slideshows that are charts for students reference throughout the lesson. Upload R controlled vowel charts, l-blend charts, diphthongs, vowel-teams. Students refer back to charts throughout the lesson. This is good for introducing phonics concepts or reviewing previously taught concepts.

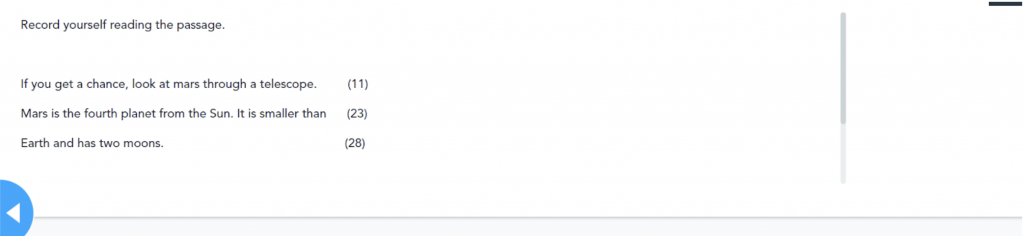

- Use Open-Ended questions connecting the sound a phoneme makes with its grapheme (written form). Record a sound through the audio feature, and students write the spelling in an open-ended question. Also, students practice full dictation skills where teachers record themselves saying a sentence and students write what they hear.

3. Fluency

Fluency is all about reading like how people talk. The only way students become more fluent readers is by having multiple opportunities to read while also experiencing what fluent reading sounds like. All of these activities give students much needed practice to help with accuracy, speed, and expression. Whoopie!

- Audio Open-Ended Questions practice. Have students record audio of themselves reading a passage in the open ended question to you. To help with timed assessments, add a time limit to better prepare students for timed running records or other timed Daily Oral Reading Fluency assessments.

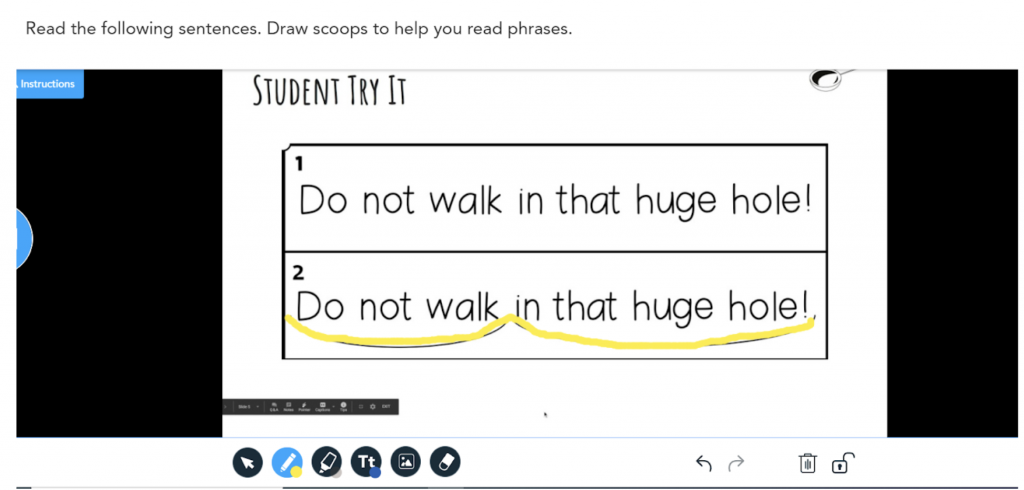

- Use Draw It for students to practice “Scoop Phrases” technique. Upload sentences where students have to group words together to train their eyes to read phrases instead of word by word. Students mark the sentences up, then read the phrases aloud.

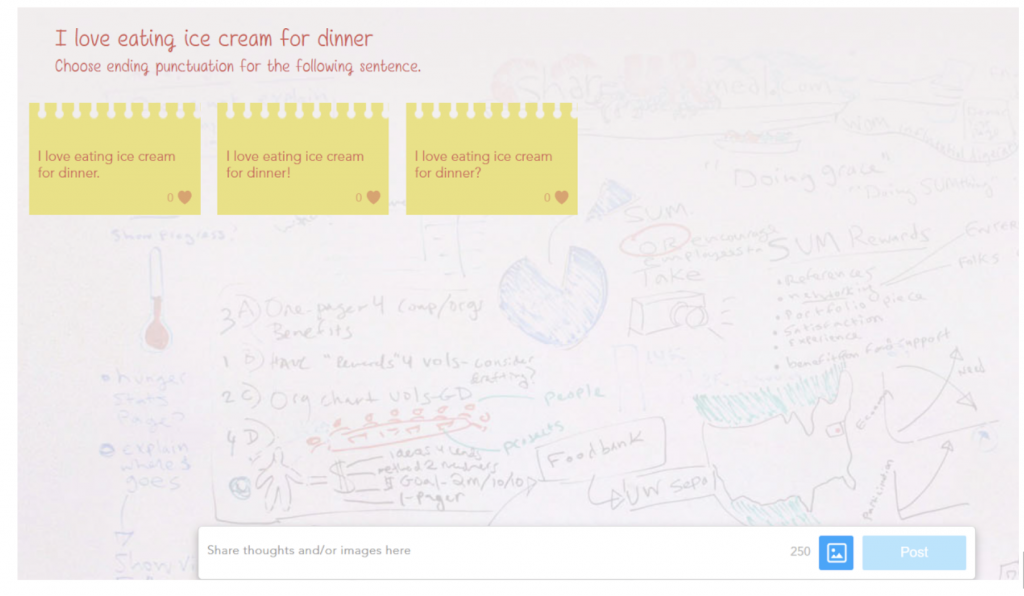

- Use Nearpod’s Collaboration Board for practice with punctuation. Write a sentence without any punctuation and have students decide what punctuation would be best and the students read the sentence depending on expression – voice raised at the end for question mark (?), passion with exclamation point (!), or even a calm tone for period (.). This activity helps students realize that ending marks tell us how to read with expression.

- Insert videos of Read Alouds into lessons for students to hear what fluent reading sounds like. Adults reading stories aloud help model expression, pace, and phrasing.

- Use Drag and Drop to create nursery rhyme, poem, or sentence puzzles for students to put back together and read. By breaking those rhymes apart into individual words and putting them back together again, kids see how words build into sentences and stories in a natural flow.

Writing ‘is a powerful lever for helping our students learn to read profoundly’

Pam Allyn, senior vice president, innovation & development, Scholastic Education, is a leading literacy expert, author, and motivational speaker. In 2007, she founded LitWorld, a global literacy organization serving children across the United States and in more than 60 countries, pioneering initiatives including the summer reading program LitCamp and World Read Aloud Day:

Writing and reading are not just two sides of the same coin; they are profoundly related and entwined. I have often said that reading is like breathing in, and writing is like breathing out—the child is taking new breaths in this new world, feeling her power and her potential.

Surrounding our children in the sounds of language from literary and informational text is crucial to their understanding of language. The child who is read aloud to multiple times per day, week, month, and year is already realizing the sound and feel of language. Then, too, the child who is given the opportunity to put her first marks on the page is already beginning to make meaning in the world. When reading a book, she sees it as something constructed from a world she already knows because her scribbles connect to those of others and give her the powerful idea that she has a voice.

Writing early and constantly, in and out of school, is a powerful lever for helping our students learn to read profoundly. Here are five ways writing supports reading and vice versa:

The student who writes becomes alert to the structure of sentences, the rhythm of multiple words together, and words that surprise. Because our students are using the tools of language to build their own stories, they are awake to the qualities of texts. When students share works by authors such as Jacqueline Woodson or Naomi Nye, they’re astounded and try to emulate them in their own writing.

Students who write quickly learn the necessity of genre. My 1st graders were writing informational texts and choosing their own topics. One wrote about nursing homes because that’s where her grandpa was. Later, I saw her scouring a book with a glossary in it. She explained, “I want to add a glossary to my story. My readers might need to know some of the big words I use to describe where my grandpa lives.” Genre is already embedded within her at the age of 6.

Students who write understand that by telling their stories, they’re making their thoughts permanent, which leads to a hearty respect for the text, the authors who write them, and the uses we make of them. When our student writers are finishing works to put into the classroom library, they have an opportunity to see themselves side by side with published works, which feels celebratory. Writing, theirs and others, inspires and connects them.

Even the smallest writer has big ideas. My 2nd grade class once wrote letters to the entire neighborhood inviting them to come see our play. People young and old came, and students saw how they could change their communities with the power of their own words. So, when they read, they consider all the ways writers can change people.

The student who writes is building confidence, courage, and a sense of self. She is learning how to evoke emotion, keep someone in suspense, and persuade while developing her own voice, which will serve her in the future whether she’s writing a narrative or an email. When she turns to her reading, she is now more aware of the author’s voice and knows the risks the author takes. She is one herself.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

Source:

https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/05/07/reading-and-writing-understanding

https://nearpod.com/blog/6-tips-for-teaching-reading-and-writing-skills-in-any-classroom/

https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-writing-directly-benefits-students-reading-skills/2020/01